The door was a rectangle of solid ironwork and it bore a big, heavy lock. I suppose alot of doors to prison cells look like this. The lock itself was a rusty crossbar. Most locks are designed to keep people out. This one was designed to keep me in.

The peephole at headheight was covered by another bar of metal, bolted in place. It didn’t seem like it was designed to open, so I figured no one would be checking in to see how I was doing. By the time I got to the point of madly shouting out for attention the guards would be long past the point of ignoring me.

On the wall adjacent, stretching roof-to-floor, “MNLA” had been graffitied in big, black, block letters. The passing braggadocio of a since-vanquished victor.

As he unlatched the lock and motioned me through the open doorway, the guard, thin and hungry-looking, said nothing. I asked him how long I’d be confined for. No response. How long would it be before I was able to see someone from the embassy. Nothing.

I stepped past him.The room on the other side of the threshold was colder than the room behind me. Bare. There was nothing in there. No basin, no mattress, no prison library brimming with the well-thumbed pages of Penguin classics. I mean, I wasn’t expecting a copy of a Dostoyevsky novel, but I figured they might have a Qur’an or something in there.

The room was a four-walled cell with a thin film of red dust coating the once-white tiled floor. An adjoining “douche” sported not a shower but a squat toilet, the shit-hole sealed over by a plank of wood. I had nothing with me. No belt, no shoes, no book to read – not even a filthy mattress to sleep on. At once the freedom of the traveller on the road had been replaced by the inertia of the prisoner, my liberty reduced to the circular pacings of my three-by-three room. A choice between sulking in the corner of my bare-floored cell and looking out on the world from the ledge of the iron-barred window.

I was suddenly aware of an inherent falsehood in the old cliché “when one door closes another one opens”. There were no magically-opening doors awaiting me in here. No biblical Paradise. The man ushering me through the doorway was too ugly to be an angel. And even if he was some kind of desert mala’ikah then where was the garden full of houris?

Armstrong-like, with just a few short steps I had made the transition into a new and alien world. With it my horizons had been infinitely broadened, delimited only by the boundaries of these four corners. I had made the transition from the World of the Free Man to the World of the Prisoner. And, in making the transition finite, it was less in the clanging shut of the door behind me but in the act of walking (of my own volition) into the cell that this realisation really hit me. The self-propulsion of my own legs had carried me into captivity. That’s irony I suppose.

***

In the days following my solo on the North Pillar I chat, natter and relax with the locals in Garmi. All of them have become close friends. There is Amadou, my trekking guide and water-boy. There is Sooleiman, my cook. There is Idrissa, Mohammed and Ibrahim. Then there are the endless hordes of children – boys and girls alike – begging for me to take their picture (see video). They waft in and out of my small mud hut, rifling through my belongings. I count the hours in the shade with Sooleiman and Amadou, and at the base of the bed we brew sweet yellow tea.

I’ve spent a week in the massif now and though I wish I could stay longer I know that it will soon be time to go. I have two countries, a disputed region and the world’s largest desert to cross. I’m supposed to be in Casablanca in three weeks. It is late afternoon on New Year’s Day (my birthday) and by the time I return with Amadou from Kaga Tondo I know for sure that I am going to miss my deadline.

Sooleiman is ecstatic to have me. His meals are simple – “riz avec des condiments” – but he cooks with passion, sitting on his haunches in the corner of the room, fastidiously tending a fire lit from animal dung. Today, my birthday and the day of my return from the mountain, he has killed a chicken to go with the rice. With wide eyes, he watches me take a spoonful and place it in my mouth. He doesn’t hold his breath but his eagerness to please is uncomfortable. It has been three years since the last group of foreigners passed through Garmi.

“Before la crise,” he says. “Many climbers came here. But you are the first to climb for many years.” He pauses for a moment. “And we would like to erect something in your honour.”

I ponder this a moment, disturbed. Garmi is a fascinating place, but Sooleiman’s words show a darker truth of modern life in rural Africa. The growing embryo of “liberal development” mean Garmi now has a well, a school and hither-scattered signs listing all the things that USAID has given to the village.

The flocks of nomads from elsewhere graze what little grass grows near Garmi because development has given the villagers books and the French language and what need is there for tending to the flock when there is a whole “national economy” awaiting? Sooleiman’s dream is to run an “auberge” – a guesthouse for passing Western travellers treading lightly across West Africa. There are no Western travellers passing by Garmi anymore.

On the other side of the mountain, Daari (the start point of my village-to-village traverse of the massif), in the shadow of Kaga Tondo, lies in the shadow of inexorable development. There is no school. There is no French language. There is only the village. And life in the village. They do not prosper in the harsh Sahelian desert but they do not go hungry either.

As the urban core grows, like an “embryo of good”, the periphery is transformed. We are told that the meaning of “education” is “emancipation”. But with education, conversations of “daily subsistence” fall by the wayside and cash not goat’s milk becomes the currency of the day. After the djihadiste advance in 2012, Mali’s tourist economy collapsed. Sooleiman and Amadou left their village and sought out the fabulous wealth of mythical Bamako. They found nothing there but abject poverty. And now, back in Garmi with neither the promised riches nor the know-how to tend the flock they had waited for a white man to come along with fistfuls of tourist dollars and change things.

In the way that he spoke to me, it seemed that Sooleiman saw me as a person who could drastically change his circumstances. I knew he was serious when he talked about erecting a statue – and it concerned me. It seemed that in some way or another, European colonialism’s parting gift to Africa was to leave behind a discourse that despite the ruinous civil war that would engulf the continent, personal contact with someone like me was the same as a ticket out.

Or as Amadou had put it: “quand nous voyons un blanc, c’est comme l’or.” “When we see a white, it’s like gold.”

To Amadou and Sooleiman, our relationship represented an opportunity for wealth, an opportunity for a visa maybe. In many ways, the reality of the global economy and the emancipatory discourse of development had created this relationship. “Development” engulfs, like a red dwarf, all bodies that orbit it, and once it implodes, those same bodies, transformed, are sucked down, down into the black hole that remains. The black hole at the core.

A week in the massif had left with me an overwhelming sense of the grim. But with only two days left, I set off with Amadou to scout out some more climbing possibilities. In the late afternoon, we sit on the rooftop of the encampement détruit in Daari, scoping lines, plotting a skyline traverse of the massif.

A trail of dust appears on the horizon. A black ute, printed with white letters bounces down the highway. It veers right off the road, trundles through the village and pulls up at the moraine wall below the base of Kaga Tondo. A man in a black, collared shirt and a woman step out, followed by a young boy and an older man in a white boubou.

Curious, we observe these newcomers, and then, identifying the man in the white boubou, Amadou tells me that he is the mayor of Hombori. The boubou belongs to Amadou and the mayor had stolen it from him. He recounts this tale as if it was normal to have your possessions taken from you by local officials.

The man in the black-collared shirt was the commander of the local gendarmerie, Amadou explained. No one seemed to know much about him except that he was a Bembera bus-in from Bamako.

The mayor approaches Amadou smiling. “I did not know you had a white here,” he says. He offers a hand and Amadou takes it. They begin speaking in rapid Fulani. The mayor scrutinises me as they speak. I wonder if there is a “guichet automatique” sign above my head and sit in silence on the rooftop.

The man in the black-collared shirt approaches Amadou. “C’est qui?” he demands, pointing a me.

“Un canadien.”

“Est-ce qu’il parle français?”

“Yes I speak French,” I intervene with a broad smile.

“Come here.” His tone is severe, officious.

I descend the creaky, mud-steps from the rooftop terrace and stand before him.

“Comment allez-vous monsieur?” he says to me. He emphasises the “vous”. Formal French.

“I’m alright thank you.”

“Je suis la commandante de la gendermarie nationale à Hombori,” he says to me. He introduces himself with the frank self-adulation of words on a business card.

“Enchanté.” I smile. I offer my hand. He doesn’t shake it. I want this conversation to be over quickly.

“Do you have authorisation to be here?” he asks me.

I nod. I reach into my pocket for my passport and hand it to him with the visa page already open.

Like Wangel Debridu behind him, the commandant stands embossed by the setting sun, rays of light making fine particles of dust dance across his epaulets. Bureaucracy in silhouette, he flicks through the passport pages.

He looks at me. “You must come with me. You are here illegally,” he says simply.

I point him to the page with the Malian visa affixed, stamped by the border police at BKO-Sénou International Airport.

He shakes his head. “Je suis le chef de la poste à Hombori,” he reiterates in case I missed it the first time. All pfiefs demand obsequiences from time to time. He pulls a government-issued ID card from a tatty old wallet to underscore his point. “You will come with me to the post now. Where you will be charged and prosecuted.”

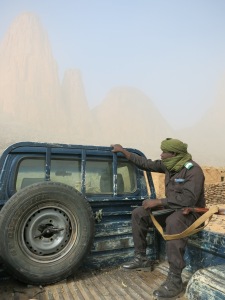

We are herded into the utility tray of his vehicle. Disturbed, I cast a look at Amadou. On the surface he seems unphased.

He shrugs. “Aller-retour,” he assures me. “We will go and then we will come back.”

A cowboy sunset hangs in the west behind the Hand of Fatima as we speed towards Hombori. Aggressive behind the wheel, the gendarme with the mayor, his wife, child and us in tow, hits every speed bump and pothole along the road.

Hombori is a nothing town in the middle of nowhere. At last light, as we approach the brigade post, a draft of wind blows red dust across the road. A duststorm gathers in the distance and the Wild West colours splashed across the sky are choked by a Martian smog.

The commandant pulls up in front of the building, a small desert fort backing onto a plain of dessicated grasses and thorn trees. He leads me and Amadou inside and we follow him down a darkened corridor into an office marked “CB” (chef de la brigade).

He switches a light on in the office and we are sat down. He is God in Hombori, he explains to me. It is illegal for me to be here without him knowing. I humour him for a time, trying the age-old ego-stroking method of escape. He explains to me that the threat of kidnapping is so high that only he can guarantee my safety and that if I had come here on the first day in the area and paid for an armed military escort (the gendarmerie doubled as freelancers it seemed) than my presence would have been legally permissible. None of the soldiers manning dozens of road blocks on the way into Hombori had explained this to me as they checked my passport, of course.

“How much would the escort have cost me?” I asked the commandant.

“Six hundred Euros,” he said matter-of-factly.

“And since I didn’t request one you say I didn’t have your permission to be here?”

“Correct.”

“And this is a crime?”

“Presque un crime,” he said, emphasising the “almost” part. He was an important guy – the commandant of an African police force at a remote desert outpost. Holding an office like that, it would be too much to grapple with the ins and outs of silly things like “what did and didn’t constitute a crime”.

I asked him how I would be punished. Lady Justice had offered me two options. I could pay a sum he referred to as “la defence” or I would be put in prison.

“How much for la defence?”

“Six hundred Euros.” There was a certain congruity in the figures he was quoting me. I wondered what his kid wanted for Eid.

I didn’t have that kind of cash and the closest ATM was in Bamako where I certainly couldn’t go (lest I be able to fact-check the offence he alleged I had committed) so he told me I would be put in prison instead. But first, I would have to “confess”.

I am sat down in a four-walled room with a tiny square window looking out on the red beyond. A gendarme is seated opposite me. He is junior to the commandant, but older than him. My interrogator.

“Vous êtes un tourist?”

“Oui.”

“Service militaire?”

“Non.” Not necessarily true but my response was a reflex and the question wasn’t relevant.

“Why are you here?”

“To climb the hand of Fatima.”

“Why are you in Mali without authorisation?”

“I have authorisation… I have a visa.”

“A visa does not give you permission to be in the country of Mali.”

I was confused now. A second man entered the room. He was to be my English translator for the confession statement I was about to make. I read French fine and of course, the English translator explained who he was in French. He said a few broken phrases in English to me about how I had committed a crime until we both silently acknowledged that his English was terrible and we switched back to French.

The first gendarme continued. “So you admit that you have done something wrong then?”

“I don’t think I understand,” I told him. “I have a visa. This is enough to be here in Mali. If you want to go to my country, Canada, all you need to do is apply for a visa from the embassy then you can visit Canada.”

“No,” the gendarme shook his head. “This is not how it works in Canada.”

“Have you been to Canada?”

“No.”

“So then how would you know?”

He pondered on this for a moment considering how and if he might know the details of Canadian immigration procedures. Then, still impervious to my bullets of logic he deflected and began firing back his own hollow-points.

“You are a spy aren’t you?” he said. Deadpan. Frankly, you had to admire him for his bluntness.

“No. I am a student and a climber.”

“How can you prove to us that you are not a spy?” intervened the “English translator” in French.

In the Gun-Toting Gendarme’s Court of Hombori, it seemed, the onus of proof was on the suspect. More to the point, there was a bona fide miscarriage of logic going on around here. How could I prove that I wasn’t something which I was not? It was like disproving the existence of God. Logically, you can’t do it – because in order to prove that something isn’t (as in “God isn’t real”) you have to know everything that is.

I could show them my student ID cards or the remnants of my climbing equipment post-Kaga to show that I was both an anthropology post-grad and an expedition big-wall climber but would that be enough to prove that I wasn’t a spy? Even I couldn’t possibly know everything about myself. Who knows… I could be a whole number of things of which I was not aware – a doomed man hiding an insidious brain tumour; a child of adoption who was actually half-Mohawk; a deluded egotist masquerading as a traveller of the world. To my knowledge however, I wasn’t in Mali spying for anybody.

It felt like a very philosophical question, one which I doubted they were capable of grappling with. So I showed them my student ID card and my membership card to the ANU Mountaineering Club and left it at that. The questions didn’t end there.

“You are a djihadiste aren’t you?” Was the next of the gendarme’s Sherlock Holmesian questions.

“No.”

“Are you are here because you have been invited to fight in the djihad?”

“No.”

I signed some statement, after correcting a few of the words he had written down as if they had come from my mouth.

The commandant burst into the room. “Maintenant,” he said. “Je vais te boucler.” He pulled a set of keys from the table. Being told that you are to be “bouclé” literally means you’re about to be “buckled and chained” which in a medieval or Alexandre Dumas novel kind-of-way seems a lot more severe then simply being “put in jail”.

“When will I be able to face la justice?” I ask, wondering if there was such thing as a magistrate around here.

“Bientôt,” is his cryptic, creepy reply. They take my belt, my shoes and my wallet from me. I am led to my cell.

Now, bewildered and alone in my new-found accommodation, I pondered my predicament. I had come here driven by some soteriological fascination with the sandstone fingers of a rock massif called the Hand of Fatima. I had come here in search of the sanctity of space, desert sunsets and stark and empty skies. The freedom of the open air. I looked around at the irony I had found instead.

A pair of finches flitted in and out of the window grate. Just as I had been imprisoned below the crux pitch of the North Pillar looking up at the birds surfing the gusts of wind, I now watched these finches, moving between my depressing wold within and the free world without. For a bird, I mused, a prison is but a perch, and a cliff but a cradle. I empathised with the birdman of Alcatraz.

With my bare toes I swept a little sleeping space in the red dust and lay down on my back, hands behind my head. The ground was cold and hard against my shoulder-blades. Time passed and with it, the sure knowledge of Amadou’s promise that we would be let go today.

I turned onto my side, my spine curving awkwardly as I jostled at once with my head on my hands and then with my bony hip on the hard floor. I felt something pinch into my right side. I reach down and felt a coin, tucked into the small watch pocket that sits zipped and stitched into the main pocket of my trekking pants. A twenty riyal coin, minted in Sana’a. A circle of gold-coloured metal girded by a ring of silver. The tails side is the number twenty in Arabic numerals and the heads side is a Soqotri dragon’s blood tree. Just two weeks after leaving Soqotra, I suddenly felt an overwhelming nostalgia for it. The “why” was self-evident.

I had nothing to do so I flipped it, asking the coin questions as a child does of those magic 8 balls. Heads was “yes”. Tails was “no”.

“Will I get out of here tomorrow?” Tails.

Fuck. Alright let’s try that again but word it differently. “Here” must have been “Mali”? And I wouldn’t be leaving Mali for another week.

“Will I get out of prison tomorrow?” Tails.

Damn.

“Will I get out of this cell by next week?” Tails.

I sighed. Alright let’s change things up a bit. Tails was “yes”. Heads was “no”.

“Will I ever get out of here?” Heads.

I’d had enough of flip-the-coin for now and I put it back in my pocket. The light went out and I was swathed in darkness. I rolled over and went to sleep.

I awoke, stomach down on the floor of my cell, and gazed out the window again. Dust filled the air – a thick and total cloud replacing the clear blue skies of yesterweeks with a drab and pale brown. The morning sun was a dull lightbulb, a sullen white circle suspended amidst the haze. With the dregs of some far-off harmattan choking the air, today would not have been a climbing day anyway but with no means to escape my earthly prison and no rays of warmth and light to brighten the morning, a sunless sense of the grim hung in the air.

I stood up again and moved over to the sill. I looked out. A nomad passed with his flock of goats, texting on his phone. Often, I had found something wholly frustrating in observing someone owning and using a mobile phone while one’s children wafted around fallow grazing grounds with swollen bellies (a tragic phenomenon worthy of a structure-versus-agency debate). But now this young nineteen year-old goatherd was my best friend.

I waved him over. Curious, at the pair of hands reaching through the metal grate he placed his cell phone in the pocket of his boubou and approached the window. “I will give you ten-thousand francs if you can call the Canadian embassy and tell them I am in here,” I said. He nodded and asked a few more questions. I gave him my details and he left.

A short time later, the commandant returns to my cell, berates me about “having spoken to Bamako” and then orders me to return with an armed escort to Garmi where I will pick up all my belongings and return to prison.

They place a pair of leg chains on me and I am led out to the ute. We return to Garmi, me, in my chains, giving the road directions to the driver. We collect my belongings and while the commandant spends a bit of time berating some of the villagers that were “harbouring me”, I snap a few photos, hide my camera and I am back in my cell and without any shoes or belt within the hour. Alone again. Alone and afraid.

The hours pass with no sign of clearing skies. The sun had gone. Dust blew across the yard. Wind scoured the dead earth. The ground under-gust seemed not to care. Submission. Giving up seemed inevitable here. Man is a social animal and alone in my cage I was neither social nor animal. I was a solitary life form without company. With every metre gained on Kaga Tondo I had felt myself leaving the world of Man but fingering the gossamer hem of a new state of consciousness. But here, in solitary confinement, though aware that I was still alive, beyond the confines of my mind I was aware only of a world outside of which I was no longer apart. I was a vegetable in suspended animation. Loneliness is a dark place to exist. Solitary confinement is torture.

By late afternoon, without any contact since our little ballad around the village, I hear the latch unlock. I stood up, walked over to the door and waited next to it, like a dog excited to see its owner. The door opened and I saw the hungry guard again, his head poking through the doorway. I tried to say something to him but he simply placed a bottle of water beside me and some food and then shut it again, saying nothing. I heard the latch lock again.

Alone once more, I looked down at my supper. There was nothing to go with the rice – just plain white grains, cooked into a mushy conglomerate with no sauce.

The sky darkened. The sun did not set because today the sun had never come. There were no lights in my cell tonight. I didn’t bother shouting out for an answer why – an answer would not be given. I roll over in the dust, and make another attempt at sleep. The desert night is a cold one and I shiver on the hard floor.

At ten p.m, the cell door swings open and the light from my headtorch shines through. I place my hand over my eyes as I adjust to the bright light shining in my face. The commandant has been going through my possessions it seems.

“What are you doing?” he says to me. “Don’t you want to leave?”

I stand up and follow him out the door, still shivering.

He sits me down in his office and explains to me what has happened. “The chief of the djihadiste rebels has called me,” he says. “I don’t know how he got my number but he has called me and asked about you.”

It was all becoming a bit surreal and farcical, like the first draft of a divine comedy that’s missing a few key pages. But then again… I’m sure that Mokhtar Belmokhtar, currently on the run from French special forces in the Algerian desert, had every reason to be on a mobile phone talking to a low-level police commander in Hombori.

“He asked if you were here,” he tells me.

I play along. “You didn’t tell him where I was did you?”

“No of course not,” he says. “But I called my superior and they informed me that we must get you out of here tonight, away from la zone d’urgence.”

I nod, feigning gratitude.

“You are to leave now, clandestinement,” he continues.

Another man enters the room – the same thin and hungry-looking guard that had led me to my cell the day previous. He is standing there in a big trench-coat, sunglasses-at-night, like some starved, schlock, Third World rendering of Morpheus from The Matrix.

The commandant introduces us. “This man will escort you back to Mopti. He will travel undercover with you and shoot anyone who tries to kidnap you.” He reaches for his desk drawer again and procures a pistol holster – the leather concealable kind worn by the protagonist of a detective show.

He hands it to Morpheus. An hour and a hundred Euros later (“for your food and lodgings”) the guard and I sit together on a bus headed back to Mopti. The commandant’s attempt at saving face in the midst of obvious pressure from above had been pathetic. But I had humoured him as a serf does his pfief and it had worked. I was out. The bus ride back to Bamako would be a long one, as it had been on the way out.

Half an hour later, as the bus passed by the massif, I peer out the window at Fatima and her hand for what I know will be the last time, the five fingers of rock a perfectly dark silhouette – blacker than the black sky. An alpenglow des ombres – what Herzog, gazing up at the nighttime skyline of the Gasherbrum range, called “der leuchtende berg” – the dark glow of the mountains.

Living up to the khamsa‘s reputation as protection against the evil eye, the Hand of Fatima had let me in, showed me her world, and then spared me from it. I’d survived the climb and a stint in prison and now I was off across the Sahara. When I left Mali, I heard that Amadou had been put in prison for not paying some bribe to the commandant to work as a tourist guide in the area. I have no way to contact him and so I have no idea if he is still in there. Voila, l’Afrique.

The Hand of Fatima massif

Pingback: Review (Film): Citizenfour | Dispatches from the Periphery